Shirali Muslimov turns 201

It was Shirali Muslimov's birthday on September 4. Yeah, I know, I forgot too. But if you didn't send a present it's ok, he died in 1973. And while it's too bad the old codger is dead, he was causing a birthday candle shortage, plus that darn cake was a fire hazard.

For a while in the 1970s, many old timers from Azerbaijan were going around claiming that they were very old. Like, really, really, ancient. This might seem strange in our youth-obsessed culture, but these people would routinely tell others that they were well over 120. I don't know why they did this. I can just imagine their conversations,

"You're 129? Well I happen to be 136 years old."

"Oh yeah? Well I am in fact am 142 and used to be Napoleon's valet."

And this sort of thing would go on for hours.

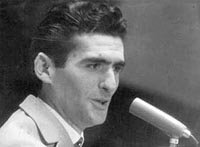

The king of these old timers was Shirali Muslimov who died on September 4, 1973 at the purported age of 168 years, allegedly making him the oldest man that ever lived, aka, the world's oldest man. His birth certificate read 1805, which made him 168 at the time of his death. He claimed to have fathered a child at the age of 136, which of course provokes some interesting questions of the who would be mating with a man of that age.

Muslimov spend his incredibly long life in the village of Barzava, 150 miles south of Baku, in the hilly Shiral region near the Iranian border. He didn't leave his village much, so you can assume that he got to see the whole town before he died.

Experts consider that the longest a human can live is 115 years old give or take a few shakes of the hourglass. But many Azeris insist that their grandmother lived to 136 or 141. The proper reply to these claims is to boast that your granny lived even older.

But Muslimov (aka Mislimov) put Azerbaijan on the map as a place where people live to a ripe old age and there is some evidence that certain people in the hills live to an extreme old age and interantional experts are still getting grants to poke around into the reason behind this.

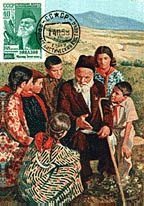

But Muslimov caught everybody's imagination. The Soviets loved this old Talish shephard for representing their claims of superiority. Danone yogourt also loved him as he inspired a successful advertising campaign attributing extreme longevity in the Caucasus to the comsumption of yogourt. National Geographic wrote about his great age, although they later recanted and suggested that he might not be as old as he claimed. The Azeri government put him on a stamp in 1994. So if all these people loved the old coot, who are you not to?

I hereby suggest that September 4 be hereafter marked by the United Nations and celebrated as the Shiraz Muslimov International Day of Longevity and Celebration of Centenarians and I think you should listen to me, as I am a wizened old man of 143 years of age.